Spherical law of cosines

In spherical trigonometry, the law of cosines (also called the cosine rule for sides[1]) is a theorem relating the sides and angles of spherical triangles, analogous to the ordinary law of cosines from plane trigonometry.

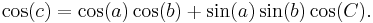

Given a unit sphere, a "spherical triangle" on the surface of the sphere is defined by the great circles connecting three points u, v, and w on the sphere (shown at right). If the lengths of these three sides are a (from u to v), b (from u to w), and c (from v to w), and the angle of the corner opposite c is C, then the (first) spherical law of cosines states:[2][1]

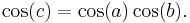

Since this is a unit sphere, the lengths a, b, and c are simply equal to the angles (in radians) subtended by those sides from the center of the sphere (for a non-unit sphere, they are the distances divided by the radius). As a special case, for  , then

, then  and one obtains the spherical analogue of the Pythagorean theorem:

and one obtains the spherical analogue of the Pythagorean theorem:

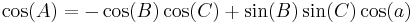

A variation on the law of cosines, the second spherical law of cosines,[3] (also called the cosine rule for angles[1]) states:

where A and B are the angles of the corners opposite to sides a and b, respectively. It can be obtained from consideration of a spherical triangle dual to the given one.

If the law of cosines is used to solve for c, the necessity of inverting the cosine magnifies rounding errors when c is small. In this case, the alternative formulation of the law of haversines is preferable.[4]

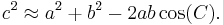

For small spherical triangles, i.e. for small a, b, and c, the spherical law of cosines is approximately the same as the ordinary planar law of cosines,

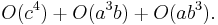

The error in this approximation, which can be obtained from the Maclaurin series for the cosine and sine functions, is of order

Contents |

Proof

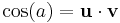

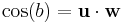

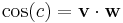

A proof of the law of cosines can be constructed as follows.[2] Let u, v, and w denote the unit vectors from the center of the sphere to those corners of the triangle. Then, the lengths (angles) of the sides are given by the dot products:

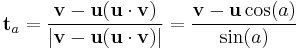

To get the angle C, we need the tangent vectors ta and tb at u along the directions of sides a and b, respectively. For example, the tangent vector ta is the unit vector perpendicular to u in the u-v plane, whose direction is given by the component of v perpendicular to u. This means:

where for the denominator we have used the Pythagorean identity sin2(a) = 1 − cos2(a). Similarly,

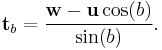

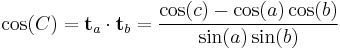

Then, the angle C is given by:

from which the law of cosines immediately follows.

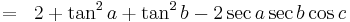

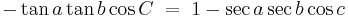

Proof without vectors

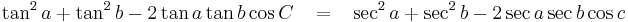

To the diagram above, add a plane tangent to the sphere at u, and extend radii from the center of the sphere O to meet the plane at points y and z. We then have two plane triangles with a side in common: the triangle containing u, y and z and the one containing O, y and z. Sides of the first triangle are tan a and tan b, with angle C between them; sides of the second triangle are sec a and sec b, with angle c between them. By the law of cosines for plane triangles (and remembering that  of any angle is

of any angle is  ),

),

So

Multiply both sides by  and rearrange.

and rearrange.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c W. Gellert, S. Gottwald, M. Hellwich, H. Kästner, and H. Küstner, The VNR Concise Encyclopedia of Mathematics, 2nd ed., ch. 12 (Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, 1989).

- ^ a b Romuald Ireneus 'Scibor-Marchocki, Spherical trigonometry, Elementary-Geometry Trigonometry web page (1997).

- ^ Reiman, István (1999). Geometria és határterületei. Szalay Könyvkiadó és Kereskedőház Kft.. p. 83.

- ^ R. W. Sinnott, "Virtues of the Haversine", Sky and Telescope 68 (2), 159 (1984).